- Home

- Michael Libling

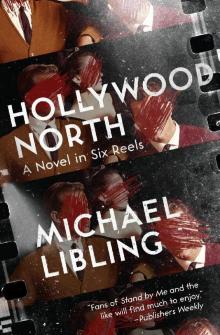

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels Page 18

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels Read online

Page 18

We did not tell Annie why, only that we thought it’d be fun. “You know, hanging out with us.”

“Doesn’t sound like fun,” she said. “You’re off your rockers. You know where I live—up in The Heights? It’s blocks out of your way.”

“We don’t mind,” we said. She had her friends to consider, though they branched off early along her route. “We’ll walk with them, too.”

Mostly, Annie confided, she was wary of the famous Jack the Finder. “He’s so full of himself. So conceited. He has never once said hello to me. And now he wants to walk me home? No, thank you.”

“You ever say hello to him?” I said.

“I’ve been friendly.”

“And when I hear kids complaining about you, saying how snobby you are, does it make it true? Are you? Just because somebody thinks something?”

“They say I’m snobby?”

I lowered my eyes, self-effacing in my deep regret. She didn’t need to know I’d never heard a mean word spoken of her. “Thing is, Annie, he wants to get to know you.”

“Honest?”

Her excited flip-flop caught me by surprise. I retracted my poor choice of words. “Yeah. Well. I mean, not like that.”

“Like what?”

“Like how you’re acting.”

“How am I acting?”

“Like you’re thinking it’s about being more than friends or something.”

“What does that mean?”

“You tell me.”

“Tell you what?”

“We want to walk you home from school. All there is to it. And, maybe, if you want, you can come to the Odeon with us. A Saturday matinee or something. We might even take you finding sometime, if you want.”

“I get it, Gus. I get it. We’re all going to be friends together.”

“Exactly.”

“Why now?”

“Why not?”

“You’ve never even tried to be friends with me on your own. Never.”

“But we are friends.”

“I’ve seen you ride your bike past my house a hundred times and you’ve never once knocked on my door. We’ve known each other since first grade, yet outside of school you run the other way. I’ve invited you to my birthday parties, my cottage, and in all the years you never came. Why now?”

“It’s time?” I ventured, feeling the heat in my cheeks.

“I guess it is. I never did understand why you didn’t want us all to be friends to begin with.” Her dimples betrayed a willful mischief. “But are you sure you’re up for it, Gus—handling two friends at once? It’s going to be a whole new experience for you.”

Eleven

The scare of ’62

In August 1962, fourteen-year-old Jimmie Orr flew with his family from Sao Paolo, Brazil to New York City. Jimmie was feverish and headachy and had been for some time. From New York’s Grand Central, the Orrs boarded the overnight train home to Toronto. Within days of arriving, Jimmie was diagnosed with smallpox and quarantined. The East Coast of Canada and the U.S. spiralled into a tizzy. Pundits and know-nothings screamed epidemic.

Trenton doubled-down on the tizzy. Fifty-five Air Cadets camping out at the base had come into contact with Jimmie, somewhere, somehow. An airlift of vaccine began. Trenton Community Gardens was converted from hockey rink to emergency inoculation centre.

Jack and I waited in the arena together, the going slow, the lines long and mobbing up. How Iris Lebel found us was anybody’s guess. “Shots won’t stop what you got,” she said, and a riptide of arms and elbows swept her back to wherever she’d come from.

“She’s losing it,” I said.

“Or trying to tell us something,” Jack said.

The smallpox scare of 1962 did not make our list. No one died. No one got the disease besides Jimmie Orr. Still, Jack and I saw the silver lining. The Unknown had given us a heads-up. Before too much longer, we’d have The Unexplained on our hands.

Twelve

Friends in a Franklin W. Dixon vein

You know by now I was no expert on friendship. My specialty was hate—a prodigy of the art by six, could’ve-been author of the how-to by twelve. Would’ve been a perennial bestseller, too. Like How to Win Friends and Influence People. Like The Power of Positive Thinking. Dale Carnegie, Norman Vincent Peale, and Gloomy Gus—the self-help triumvirate.

I knew hate when I saw it. Hate was what Annie had for Jack and Jack for Annie. Don’t tell me you would have seen it any differently.

Annie’s practice was to walk home with Susan Burgess and Diana Klieg. On Fridays, Bonnie Priddy came along, too. Bonnie was the tallest girl in school. She wore a leather brace on her left leg and carried a crutch; she’d had polio. Bonnie visited her grandmother on Fridays. “She makes the world’s best meatloaf,” she’d say. I had no grandmother. Could only imagine what a grandmother could do to meatloaf that my mother could not.

In the beginning, Jack and I lagged behind, parrying the girls’ snickers and barbs. Our presence was cause for debate and hilarity. We were theirunexplained mystery of fifth grade, a Trojan horse dragging up the rear. Annie instigated, too, alternately laughing off the attention or irritated by it. She was different with friends close by. Always was. This was not my trusted confidante, the sympathetic ear. These were the moments I liked her less, though she would predictably reverse course in private, carry on as if she’d done nothing to offend, and I’d come out the other end liking her all the more.

Jack and I accepted the abuse, unwavering in our mission, truck drivers in The Wages of Fear, Annie our nitroglycerin.

Susan would peel off first. Diana next, along with Bonnie. It’d be another half-block before Annie would drop back to walk between us, or Jack and I moved up to escort.

First day out, Annie set the snotty tone with Jack: “Haven’t seen you in the paper much. Guess you don’t find things, anymore, eh?”

Jack played shocked to the hilt. “You read the paper?”

“What makes you think I don’t?”

“I didn’t expect you’d have the time, seeing how you’re always playing with your hair.”

“Try combing yours for once, why don’t you! It’s like I’m walking The Shaggy Dog.”

She would have been nicer, I guessed, had she known we were out to save her life. I worried, too, she’d put Jack off, cause him to leave the body-guarding to me alone. Jack, to his credit, did not let the sniping interfere with duty. Week three, in fact, he invited her to his Fortress of Solitude. Yeah, just three frigging weeks. I didn’t get it. Me, it had taken months.

“You’re the first girl I’ve ever let in,” he told her. “Not counting my sisters.”

“I’m sure your sisters don’t count you, either.” Annie maintained form, impassive and unimpressed.

Jack would laugh at her insults. Not always, but often. Another thing I never quite got.

They couldn’t go two sentences without taking a shot at each other. I should’ve worn black and white stripes, carried a whistle. “Cut it out, you guys. C’mon, eh?”

“She started it.”

“Did I? Really?”

“Yes. Really.”

“Did not.”

“Did, too.”

“C’mon, you guys. Please.”

“Shut up, Gus.”

“Yeah, shut up, man.”

They had a knack for being nice to each other, without being too nice.

At some point, Annie took note of the Lone Ranger and Tonto bookends. “So what are all these, then?” she asked.

“Um,” Jack said. “Books?”

“I’d never have guessed,” she snarked.

“Mysteries,” I said, aiming to defuse. “Unexplained phenomena. Ghosts. Lost worlds. UFOs . . .”

“Interesting.” She looked to Jack. Her sweetie-pie face. “May I borrow a couple?”

“I don’t lend books.”

“I’ll be careful.”

He put her to the test. “Do you dog-ear the pages or us

e a bookmark?”

“Bookmark.”

“Always?”

She dumped the sweet. “Occasionally I tear off the cover and make origami butterflies with it.”

I laughed, elbowed Jack in the ribs. “That’s a good one, eh?”

Jack didn’t find it funny. Could be he didn’t know what origami was. To most, Japan was Pearl Harbor, tin toys, and Sessue Hayakawa. “Swear you’ll bring them back.” Had he owned a lie detector, he would have hooked her up.

“Why wouldn’t I?”

“I don’t want them getting lost.”

“Why would I lose them?”

“You’d better not.”

“What do you recommend?”

“They’re all great,” I said. I was Johnny Appleseed, casting joy wherever I went.

Jack grabbed a Hix and a Ripley. “Start with the easy stuff.”

She rebuffed him, crouched for a closer look at the titles. “This one,” she said. “And, uh, this one.”

Atlantis: Found! and Weird, Weirder, Weirdest! “Good choices,” I said, though any would have been.

Jack added his original recommendations to hers, opened a notepad, marked down the titles and the date.

Annie smirked. “Will I be fined if I return them late?”

Jack never did collect on late fees. Annie returned the books and borrowed more. After the third lot, Jack stopped keeping a record.

She loved the books as much as we did. “I can’t get some of these out of my head. The boy with the clock eyes, for instance . . . So weird. Are they true? Do you guys believe them all?”

“Not all,” I said.

“Most,” Jack said.

“They don’t teach us any of this in school.”

“Another unexplained mystery,” I said.

“But Oak Island. You’d think we’d learn about Oak Island. It’s in Nova Scotia.”

“Mahone Bay,” I said.

“Or the ghost stories. Some of these have to be real. So many of them.”

“The Marfa lights.”

“Raining cats and frogs.”

“Divining rods.”

“You try asking adults about this stuff and they look at you like you’re nuts.”

“Most religious people don’t believe in the supernatural unless it’s in the Bible,” Annie said. “I think they should, though. The more strange things that happen in this world—like in these books—the firmer a person’s faith should be, don’t you think? God is supposed to work in mysterious ways, isn’t He? Everybody says so. Your books—there’s enough there to persuade the dumbest nonbeliever.”

Theirs was not real hate. I saw soon enough. Real hate is easy to keep up. Done correctly, it’ll follow the hated into their grave, allow you to dance a little.

Whatever Jack and Annie had against each other, it ebbed and flowed. I never could put my finger on it. Stopped trying. I wanted the three of us to get along. Nothing more. Frank Hardy, Joe Hardy, and Iola Morton—aFranklin W. Dixon friendship. Spanky, Alfalfa, and Darla. Clark Kent, Lois Lane, and Jimmy Olsen.

“Show me the best thing you’ve ever found,” Annie said.

The garage had become our de facto clubhouse, the status official when Jack added a third chair for our newest inductee. A folding lawn chair.

“The best thing isn’t here,” Jack said, too quickly for our own good. And hers.

I matched his recklessness with my own. “Why don’t we show her already, Jack?” And then to Annie. “They’re at my—”

Jack hissed through bared teeth. “You lost your mind?”

“Your fault,” I told him. No way he was going to pin this on me.

He backtracked for Annie: “My best find ever was stolen. The message in the bottle from the James B. Colgate.”

I took the cue. “It was a ship that sank in Lake Erie.”

“A sailor from Sweden wrote the message. It was to his wife.”

“He drowned,” I said.

“In 1916.”

Annie was awed and moved. “That’s so sad.”

“Yup.”

“Yup.”

“Who stole it?” she asked.

“Some jerk,” Jack said. “Called himself Cardiff Mann.”

“Junior,” I added.

“You can read about it over there.” He directed her to the bulletin board. “The clipping on the bottom right.”

Annie read enough to get the idea. “That’s terrible.”

“No sense crying over spilled milk,” Jack said, the unassuming hero.

Annie scanned the other clippings. “Bryan McGrath writes about you a lot. Him and my dad are friends. They go hunting.”

Jack and I didn’t know what to say. Hearing Annie speak the reporter’s name gave us the willies.

“Yeah, that bottle was so neat,” Jack said.

“One time I put a message in an Orange Crush bottle and dropped it into the bay,” I said.

Annie gave us a skeptical once-over. She dropped her hands to her hips, recast them as fists. “I am sick of you both. I am fed up with you treating me as if I am stupid. If you want to be friends with me, you had better stop. I want the truth and I want it now. What was it you wanted to show me?”

Jack gulped. “That was it.”

“Yeah, the bottle.” My smile was so massively fake my lips should’ve ruptured.

“Peas in a pod. Rotten peas in a pod. You, Jack Levin— you’re as bad a liar as Gus.”

Dragging Annie into the mystery of Hollywood North was what we’d been looking to avoid. Alluding to the cards was dumbass, and I kicked myself for it. Even if Jack was mostly to blame. Keeping Annie in the dark was how we kept her safe. Or so we hoped. Jack and I were in the dark, too. But Annie’s was a darker dark. Her best defense was ignorance. And it was here she put herself at greatest risk. Because ignorance was not anything Annie settled for. Sure, skeptics might’ve scoffed, pointed to her faith in God, Jesus, and her nine sibling angels as proof of her ignorance. But not me. Not ever. Annie came to her own conclusions. I’ve thought about this often over the years. Her belief in a Higher Power was not ignorance; it was conviction arrived at from what she called “faith-based evidence”—sunrises, sunsets, first breath, and last. To Annie, faith synthesized the deductive and the inductive. Miracles were not an abstract; reality itself was the miracle. “How can anyone not see?” Faith was the absolute and binding logic that Science, in all its blinding logic, was too rational, too pedantic to see.

Annie’s belief gave me the strength to question my disbelief.

Annie did not back down. Anytime and anywhere, her demand was as reflexive as hi and bye and God bless you: “Show me the best thing you ever found.”

Jack and I had slipped up.

“Show me.”

She saw right through us, knew we were hiding something. “Show me.”

She persisted and we resisted.

“I told you, Annie.”

“We told you, Annie.”

“I’ll stop asking when you two stop lying.”

The girl was out to wear us down.

“Show me.”

Thirteen

McGrath on the hunt

Annie was one of us now, and we wrestled with the unfairness. “She’s either full-fledged or she’s not,” Jack said. “We should tell her. McGrath hasn’t been on our backs for weeks.”

“You think he’s gone away?” I sputtered. “He’s coming for Sunday dinner. To my house.”

“Your mom really likes him, eh?”

“She doesn’t know him. Not like we do.”

“Soon you’ll be calling him Daddy.”

“Shit, you think I’m not worried?”

“You can’t let him into the den—your father’s books . . . If he starts snooping around . . .”

“Jesus, Jack, I’m not stupid.”

“I enjoy his company. He’s an interesting man.” My mother assured me they were friends and nothing more. “Bryan is old enough to be my father. Gra

ndfather.”

“When has that ever stopped you?” I said.

“Pardon me? What did you just say?”

“I don’t like him.”

“If I listened to you, I wouldn’t have a friend in the world.”

“I liked Dottie.”

“How does that have anything to do with Mr. McGrath? One does not cancel out the other.”

“He smells like tobacco.”

“If I based my friendships on who smokes, I’d eliminate ninety percent of the people I know.”

“I don’t like him.”

“Oh, my! You won’t let up, will you? You get so angry when I choose friends for you, but it’s okay for you to choose for me?”

“Jack’s mom is nice. She can be your new Dottie.”

“Mollie Levin and I are friends. Good friends. But it’s different. Different with Mr. McGrath.”

“He’s not your friend.”

“You can’t have me all to yourself, Leo. I have a right to a life, too. I’m warning you, you be polite to him. He’s a writer. You can learn from him. Didn’t you say you wanted to be a writer, too?”

“I want to be what Dad was.”

“You don’t have a clue what Daddy was. I barely know.”

This was a revelation. “I thought you said he was a . . . a . . .” Jesus. In all these years, I’d never asked and she’d never stepped up to say. His books, his age, the freaky circumstances of his death—this was the sum total of my knowledge of him, the material on Alexander Berry so lacking, my mother had been unable to build a convincing mythology. She’d left the job to me, and the bio I’d concocted didn’t go much beyond blood on a toilet floor.

“He did something,” she said, floundering as I floundered. “Something to do with insurance. Or importing and exporting. He was vague—what can I say? Your daddy was not a talkative man. He preferred to read.”

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels