- Home

- Michael Libling

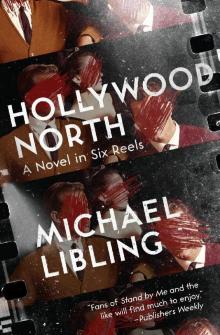

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels Page 19

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels Read online

Page 19

“He wore a suit to work. A tie. Right?”

“Always. You’ve seen the snapshots.”

Okay, then. All was not lost. He wore a suit, a tie, and did something. My father was a TV dad.

“He was a good provider, Leo. He didn’t leave us high and dry like so many men do to their families.”

“He fought in the war, too, didn’t he?” Ward Cleaver had been in the Navy. The Seabees. Mind you, I’d seen no pictures of Dad in uniform.

“Of course. He was very active. I’m sure he was.”

Dinner began with hollowed-out oranges carved into baskets and filled with fruit cocktail. Then cream of tomato soup, Swedish meatballs, mashed potatoes, green peas, and red cabbage mixed with something redder.

Mom asked Mr. McGrath about his work.

“Did you see the piece I did on that old lady? Incredible. A hundred years old and square dances every Tuesday.”

“I should be so lucky,” Mom said.

“You’re perfect the way you are,” McGrath said, and I harpooned three Swedish meatballs with my fork.

“Did I mention Leo is friends with Jack Levin—the boy who’s always finding things?”

McGrath slapped a thigh. “Well, isn’t that interesting! Jack’s a fine boy—though his finding days would seem to be behind him. A long while since I’ve heard from him, though I see him at the restaurant often enough. Hard worker, he is.”

“The Levins are wonderful people.”

“And what about you, Emily? How goes the door-knocking?”

“I can barely keep up, I’m so busy.”

“I told you, one of these days I’m doing a feature on you. Beautiful young widow becomes a cosmetics tycoon.”

Mom blushed. “Stop it. Just stop it.”

“Yeah. Please,” I said.

“Aha, Silent Sam speaks. So, your mother tells me you want to be a writer?”

“You should show Mr. McGrath the story you wrote for school—the one about the forest fire and the wolf.”

“I threw it out,” I said, and jumped up from the table in search of ketchup.

“Lovely. Just lovely, Emily. Haven’t had a home-cooked meal this superb in years. A man could get used to this.” McGrath’s wink was for my benefit, as I returned from the pantry.

“I’m so glad you enjoyed it.” Mom beamed.

“I’ll bet you could work wonders with venison.”

“I could certainly try,” Mom said, “if I knew where to get some.”

“Oh, I might be able to arrange the occasional tenderloin.” Now the asshole winked for Mom’s benefit.

“You ever watch The Real McCoys?” I said.

“Can’t say I have, son.” McGrath’s brow furrowed with interest.

“You remind me of Grandpa McCoy.” I gave the bottom of the ketchup bottle three hard whacks. “You know, Walter Brennan.”

Mom kneaded her forehead, smiled with all her teeth and gums. “Give me a few minutes to clean up. We’ll have dessert and coffee in the den. Show Mr. McGrath the way, Leo. I am sure he will have much to say about the books.”

“Books?” McGrath pushed back from the table. “Now you’re talking.”

“Why can’t we have dessert here?” I said. “Or the living room?”

She glared. “Because it will be nicer in the den. Dear.”

I walked a fine line. If I protested too much, he’d sense I was covering up and sniff out the cards in a flash. I had to be protective, just not overly or obviously. Where the hell was Jack when I needed him?

Our den was a drunken hexagon. No two walls shared the same dimensions, which made the room something other than a hexagon. Oak bookshelves were built into five of the walls, the sixth a leaded bay window. Dad’s walnut desk dominated the study. Two pedestals, nine drawers, and a writing surface inlaid with gilded leather. Behind the desk, a leather chair on rollers. In front, two leather armchairs dotted with brass studs. A Persian carpet of red, blue, and gold flowed from under the desk, traversing the dark hardwood floor to within a yard of the door. A sparse array of relics took up the perimeter of the desktop: Dad’s circular pipe stand, five pipes and a humidor in the centre, his silver letter opener with the ivory handle, a pewter ash tray, and a desk calendar forever flipped to December 1954.

“Lord love a duck!” McGrath squawked, and bounded toward the widest shelf. “Quite the collection.” He tilted his head to align with the spines. “Would you look at these!”

“They’re my dad’s,” I said, conveying lineage, ownership, possession, caution. “They’re my dad’s.”

“A voracious reader, indeed. Wish I’d known the man. We would have had a considerable amount in common, your mother notwithstanding. Ah, look at this, a John James Audubon—”

“Don’t touch it. I told you, they’re my dad’s.” I improvised on the fly, invoked my Village of the Damned persona, segued to the toxic Twilight Zone kid—the boy who turned a neighbour into a Jack-in-the-Box for playing a Perry Como record. I’d enlist the pigtailed murderer from The Bad Seed, too, should it come to that.

I edged toward the desk and letter opener. Plotted. I’d drive the blade into his neck. Or his heart. Or his brain. Yeah, straight through an eye and into his brain. I’d claim he tripped, recycle Mom’s alibi from Malbasic and the bronze owl incident. “They’re my dad’s,” I repeated, hardnosed and hardline. I squared my stance, hands on the desktop behind me, feeling my way to the letter opener.

McGrath swirled his tongue from cheek to cheek, assessing me. His hand wavered over the Audubon. I couldn’t tell you where every intertitle was buried, but there was one in the Audubon, damn sure. I’d slipped it between the birds myself.

“Here we are, then,” Mom trilled, arriving with a tray.

“In the nick of time,” McGrath exclaimed, and winked his bullshit wink yet again, his nick dangling between me and dessert. He unwound into the nearest armchair. I took Dad’s seat behind the desk. Mom sat in the armchair kitty-corner the prick.

She poured coffee, while I claimed the chocolate milk, a facile attempt to placate; she never let me have chocolate milk with dessert. “Too much sugar and the flies will eat you up.”

She spooned apple crisp into cut glass bowls and topped each with whipped cream.

I had no appetite, toyed with the mush, sculpting, digging.

“You’ve outdone yourself, Emily.”

“Easiest dessert ever.” Mom was way too happy in the moment and I worried for her. A fall was coming. It had to be. McGrath or me, one of us would knock her from the peak.

“You were so right about the books,” he said. “Love to get my hands on some of these.”

“They mean a great deal to me,” she said, transitioning to wistful.

“That Audubon could be worth a tidy sum. A first edition a sizeable fortune. Indeed, several of these would have value to collectors.”

“I’d never sell. I couldn’t.”

“It’d be important to know. At the very least for insurance purposes. Be a shame should something happen and you came away with nothing.”

“Who’d have thought?” Mom said, raised an eye, flared her nostrils, her way of saying, “I told you so, Leo, he is a decent man.”

McGrath stroked his chin, returned to the shelves, perusing and pondering. But he didn’t touch, which was all I cared about. He squatted, occupied with the doings on a lower shelf. “Whoa, whoa,” he said. “What have we here?” And I thought uh-oh.

“Another bankable Audubon?” Mom said cheerily.

McGrath swung up and about with a suddenness I’d only seen from TV lawyers. “Was your husband a Red, Emily?”

“What?” Mom said, uncomprehending.

“A communist?”

“Alex?”

“I’m not accusing, only entertaining. Were his views what you might call radical?”

“I’m not sure I—?” She’d gone pale, which took some doing. In the fairest-of-them-all rankings, Snow White wouldn’t have had a

prayer against Mom.

“Several of these—this shelf particularly—have a distinctly pinko bias.” Clean, snatch, and jerk, McGrath finessed the books onto the desk, a full house of sedition.

Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell

The State and Revolution by Vladimir Lenin

Ten Days that Shook the World by John Reed

Reform or Revolution by Rosa Luxemburg

Socialism: Utopian and Scientific by Friedrich Engels

My stomach rear-ended my tonsils. My worst fear realized. Pressed to the back of the shelf from where he’d taken the books, as plain as the nose on Jimmy Durante’s face, was an intertitle. A fucking intertitle.

Were I at the Odeon I would have snorted aloud at the implausibility—any plot in which any villain, no matter how self-absorbed, could have missed the card.

“Alex never spoke of politics,” Mom said, and I feared she might cry. I was stressed enough, without her tears stoking the anxiety.

“Alex. Alexander. Not an uncommon name in the Soviet Union. As for the Berry, now, I wonder . . . Bershov? Berezin? Berezhnoy?”

But my mother did not cry. Not a tear. “This is idiocy,” she said evenly, angrily. “Where are you going with this? Why are you doing this, Bryan?”

“Now, now, Emily. Please. Please.” The scheming bastard was beside himself. “I have upset you. This was certainly not my intention. Oh, my dear, I am so terribly sorry, you must believe me.”

I loved it. McGrath had showed his true self sooner than I could have hoped.

He perched on the edge of the desk nearest my mother, lit up a cigarette. Like he’d done to Jack and me at the Record. He gathered her hands into his. “My intent was never to point fingers. I was merely intrigued at the possibility. I am first and foremost a journalist, don’t forget. I am confident, if anything, your late husband’s interest was academic. At worst, he was a fringer—a fellow traveller. Trenton has its share, trust me.”

My mother bit her lip, withdrew her hands.

“But then how many real commies own Audubons, eh? Let me see if I can’t brighten your day, find out if yours is as valuable as I suspect. You could be a very wealthy young woman, Mrs. Berry.”

His back was momentarily to Mom and me as he searched for the Audubon. No way he wouldn’t see the commie shelf and exposed intertitle. No way.

My arms an oval upon the desk, my head resting upon a shoulder, I corralled the letter opener, glimpsed my mother’s state of being, witnessed her destiny in the glisten of her eyes, and over the desk I leaped, by God and Country, and pumped and pumped and pumped that letter opener into McGrath’s neck till his head was bobbing from a fleshy thread.

Oh, boy. How I could’ve.

My arms an oval upon the desk, my head resting upon a shoulder, I corralled the letter opener, glimpsed my mother’s state of being, witnessed her destiny in the glisten of her eyes, and initiated my unplanned plan B.

I stuck two fingers down my throat and the Krakatoa of my gut erupted. Hell, I thought I’d lose my teeth, the velocity of the vomit surging upwards and outwards with a force I’ve not encountered since, a tsunami of Sunday dinner, waves of red cabbage and what might’ve been red berries.

Into my apple crisp.

Onto my father’s desk.

Onto my mother’s lap.

Into McGrath’s coffee and onto McGrath’s shirt, trousers, shoes. I’d snuffed his cigarette!

“Oh my, Leo.” Mom dodged as I spewed, rushed to my aid, a wad of napkins at the ready, mopping and blotting.

McGrath was on his feet, flicking the barf from his hands, stomping it from his feet, helpless as the ooze descended into his waistband.

“I’m sorry, Bryan.” Mom didn’t sound sorry. “You should go now. Really. I’ll pay for your dry cleaning.”

“The boy is disturbed, Emily. He belongs in boarding school. A military academy. I’m telling you, for his own—”

“Yes. Thank you. I’ll be sure to give your suggestion all the consideration it deserves. Now, if you don’t mind . . .”

After Mom had gone to bed and the house was quiet, I put some distance between the intertitle and Dad’s commie books, transplanting the card to a higher shelf and The Voyage of the Beagle. On the off chance Mom came around and forgave McGrath, I didn’t expect he’d have much interest in a book about a travelling dog.

Fourteen

Annie in the Lois Lane

Jack grabbed my shirttail as Annie and her pals sprinted ahead. “She doesn’t want us walking with her. She’s sick of us treating her like a girl.”

“But she is a girl,” I said, confused why she’d suggest otherwise—and when and where Jack had spoken to Annie without me around.

“She’s fed up with our lying to her. I came this close to telling her what’s what.”

“Not after last night. You can’t. I told you, McGrath is as bad as ever. You should’ve seen him. He shook my mom up good. . . . One second he’s Rock Hudson with Doris Day, next he’s calling my dad a commie.”

“Your dad was a commie?”

“I dunno. Maybe. McGrath said some of his books—”

“Wow, like a Russian spy?”

“More like Herb Philbrick, I’m thinking.”

“A communist for the FBI.”

“Yeah, but then the commies found him out and killed him.”

12:00 4 I LED THREE LIVES—Espionage

FBI counterspy Alexander Berry, family man insurance salesman, and importer/exporter, infiltrates the American Communist Party, foiling Communist plots and unmasking those who would destroy America.

“I thought your father died on D-Day.”

“That’s what they wanted us to think.”

“Who?”

“It’s top secret, man.”

“You are so full of it, Gus, it’s coming out your ears.” That was Jack for you. Robert Ripley and his cohorts could issue any manner of outlandish claim, but mine he pooh-poohed.

“Yeah, well, this isn’t about my dad, okay? We’re talking Annie, remember? And say we do tell her about him, the intertitles, Hollywood North—then what? She tells her dad, her dad tells McGrath, and McGrath . . . Jesus, who knows what?”

“You’re sure he didn’t see that card?”

“How many times I gotta tell you?”

“Must have been a sight—your puke all over him. . . . McGrath is more batshit crazy than the old coots he warned me to be wary of.”

“So what are we going to do?” I said.

Annie looked to see if we were following, wrinkled her nose in annoyance, threw up her hands and waved us off. What could Jack and I give her, satisfy her need to know without putting her in any more danger? How much did Clark Kent tell Lois Lane, for instance, to allay her suspicions he was Superman?

A Variety Pack of neuroses collected mold in the pantries of our brains. Sugar Frosted Death. Rice Creepies. Nabisco Shredded Guts. Cap’n Crunch Your Bones. Neat little boxes of assorted anxieties, and plenty to spare. “What if we threw her a few bones,” I said, “without bringing McGrath into it?”

We waited for her friends to go their separate ways and sped ahead before Annie had the chance to flee. Nose up. Chin out. Jaw set. She would not look at us. “Get lost.”

“We’re going to show you,” I said.

“You need to understand,” Jack said, “it’s not anything we’ve found that we’ve been keeping from you, it’s something we’ve found out.”

“We didn’t want to scare you,” I said.

“That’s what I hate about boys. Because I’m a girl, you think I scare more easily than you. Tell that to Joan of Arc. Or Amelia Earhart. Or Florence Nightingale. Or . . . or . . . or Marilyn Bell. I’m no more frightened of anything than you. Probably less.”

“We’ll see,” Jack said.

“You will,” she promised.

“Annie Oakley was pretty brave, too,” I said.

“It’s in the name,” Annie said, and fired off a broadside o

f Annies, Anns, and Annes, three of whom I’d heard of: Ann Blyth, Ann-Margret, and Anne of Green Gables.

Fifteen

Sideshow for the darker plan afoot

“You wanted to see the best thing I’ve ever found,” Jack said.

Annie stationed herself by Jack’s garage door. Her schoolbag hung from her shoulder.

“Except,” I said, “we don’t know why it’s the best.”

“Not yet,” Jack said.

“But we will,” I said.

“Get on with it or I’m leaving,” she said. Earning our way back into her good graces would take some doing.

Jack flipped to a page in a spiral notepad, passed it to her, and returned to his work table.

She read. Pondered. Frowned. Double-shrugged. Clung to her suspicion like it was a life raft. “If you ask me, you guys spend too much time at the Odeon. I’ve never heard about any of this.”

“Us neither,” I said. “Until we did.”

“These things, Annie, they happened here, in Trenton,” Jack said. “All of them.”

“So what?” she said. “Accidents happen everywhere. Crimes.”

“Yeah, but everywhere else they remember the bad stuff. They talk about it. Put up memorials or whatever.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Neither do we,” I said. “Not yet, anyhow.”

“You do realize what you’re saying,” Annie said, and huffed. “If what you claim is true, and no one remembers these things happening, how is it you do?”

We explained what had been going on, how we came to make the list and our inability to connect the dots, the so-called amnesia.

She was adamant. “People do not forget things like this. They just don’t.”

“Unless they just do,” Jack said.

“It’s The Shadow,” I said. “He’s come to town and clouded everybody’s mind.”

“Except yours, of course. And Jack’s,” Annie said. “‘If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?’”

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels