- Home

- Michael Libling

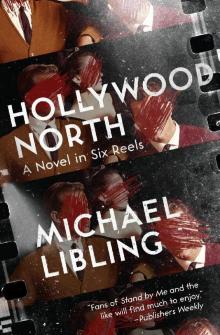

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels Page 17

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels Read online

Page 17

“My dad and him, they were friends,” I said.

Eight

Cause for optimism at last

While Jack and I were burying the cards, a speedboat smacked into the concrete pier at the town marina during time trials for upcoming races. The driver of the speedboat died on impact. They had to scrape him off the dock with squeegees. Six bystanders were injured by flying debris. Five would be dead by month’s end. The sixth lost her eyes and an ear.

The driver was Dr. Cornish. “He was my dentist,” Jack said, and added the accident to our timeline.

“Do you think we’ll forget?” I said.

“That this happened?”

“It’s how it should work, if we’re like everybody else. . . .”

“I hope not.”

“But we wouldn’t know, would we?”

“That’s what forgetting is. Not knowing. And not knowing is as good as never happened.”

“What if one of us remembers and not the other?”

“It’d be like half of us dying.”

“Or half of us gone crazy,” I said.

Nine

Into the din and the glare

The Thursday after that eventful Saturday, Mom and I were having dinner at the Marquee. Mom had reason to splurge. In the two weeks she’d been at it, her Avon business had taken off faster than anyone could have anticipated. She was loving it. “It doesn’t feel like selling. It’s more like chatting.”

I’d just pulled the toothpick from the second quarter of my turkey club when Jack gave me this anxious look and the restaurant door swung open.

Bryan McGrath hailed Jack’s dad as only a café regular can. “What’s cookin’, Bert?”

Mr. Levin fired back from his post at the grill: “What’s the scoop, Mac?”

“Five cents and you can read it in tomorrow’s Record.” McGrath chuckled and settled in at the table by the window. You would’ve sworn he owned the damn joint.

He summoned Jack with a curt two-finger wave and the grizzled specter of Robert Service reared its head once more, the lines reeling ominously through my skittish brain: When out of the night, which was fifty below, and into the din and the glare, There stumbled a miner fresh from the creeks, dog-dirty, and loaded for bear.

Mom was yammering on about my school day, about her day at work, her lunch, her customers, her district manager, her best-selling shade of lipstick, and this wonderful article about what’s wrong with TV she’d read in Reader’s Digest, but my focus was Jack and the reporter. Not that I could hear a word. I had to wait for Jack to fill me in.

“You talked to Norman Blackhurst.”

“I brought my dad’s shirts in for cleaning.”

“Don’t lie to me.”

“I’m not.”

“What did the old fool tell you?”

“Thursday. He’d have the shirts on Thursday.”

“You think I’m an idiot, Jack?”

“I’m not thinking anything, sir.”

“That man, he’s not right in his head. Imagines things. Hallucinates. You best forget whatever it was he told you.”

“But my dad already picked up the shirts.”

“Now you’re a comedian, eh? You disappoint me, Jack.”

“What is it you think he told me?”

“Ha! You’re good, kid, I’ll grant you that. You and your pal take care of the business we discussed?”

“I can show you the ashes.”

“Neither of you tempted to keep a souvenir?”

“Swear to God,” Jack said. He crossed his legs at the ankles to ensure God’s forgiveness for implicating Him in the lie. God would understand, survival at stake.

McGrath clicked his tongue like he’d just cocked a six-shooter. “Always knew you were a bright boy.”

And for no reason he could explain, Jack cracked: “I know about Hollywood North, the movies. Why’s it all so secret?”

“Blackhurst. I knew it.” McGrath’s mouth withered dry and small. “Demented old fuck.” The sinews of his neck skewered his skull. He dragged his eyeglasses the length of his nose, folded them into his shirt pocket. He was shaking, his every word a hardened turd: “How ’bout you fix me a nice slice of your mom’s apple pie? A wedge of cheddar. Cup of joe. Black. Three sugars.”

Jack’s chest was heaving as he passed our table. “I’m so glad you boys have become friends,” my mother said.

“Me, too,” Jack and I said in unison.

Jack filled McGrath’s order, set the pie and coffee on the table. The reporter clamped wiry fingers onto his wrist and from behind the cover of a Karloff grin, he said, “Let’s you and I go hunting one of these days. I’ll set it up with your dad. I got this elephant gun—what a beaut!—same weapon Frank Buck favoured. You know Frank Buck, don’t you? Big-game hunter. Crack shot. Ice water in his veins. Could take a rabid rhino down at twenty paces and never break a sweat.” McGrath called across the floor to Jack’s dad. “Hey, Bert, Jack here wants to know if you’ll let me take him hunting one of these days. What do you say?”

“It’d be an honour,” Bert called back. “He couldn’t ask for a better teacher.”

Jack faked a smile, said, “I don’t know what you want me to say, Mr. McGrath.”

“Look, son, a person digs up the past, next he knows—no future.” He let the message sit. The threat was direct and left Jack speechless. “I know you love your family, son. But what about this town? You love it, do you?”

“What?”

“Trenton? Do you love it?”

“Sure. It’s okay.”

“I’m on your side, son. I see kids playing with dynamite, I take away the matches. You need to understand: sometimes the truth is less credible than the lie. You let it out of the bag, they stick you in a straitjacket. Need be, they put you down like a mad dog. Am I making myself clear?”

“Yes.”

“I am telling you for the last time, stop before you’re sorry. Because you have no idea how sorry sorry can be.”

McGrath lightened his grip. Jack reclaimed his hand, and retreated before forced to go another round.

He secluded himself at the sink, washing and scrubbing, beating up on dishes. Glanced over. His face blank. Caught my eye. Mouthed: “Oh, shit.” And not ten seconds later, a shake of his head and a larger: “Oh, shit.” The worries I’d suppressed boiled to the surface. Was McGrath about to make good on his earlier threats?

The reporter polished off his pie, smoked, nursed his coffee, kibitzed with Bert and fellow regulars. Everyone knew Bryan McGrath. McGrath was a good guy. Like Dougie Dunwood and Vlad the Impaler were good guys.

My stomach made a break for my throat. The guy was waiting for Mom and me to finish up so he could follow us home and finish us off. I was sure of it.

I ate slower.

Way slower.

We were getting to our desserts when McGrath stood to leave. Without warning, he lunged for our table, slid across the surface, and plunged his fork into my mother’s heart, so deep it went clear through to her back, emerging below a shoulder blade, a morsel of apple pie undisturbed on the tines.

In some ways the reality was worse.

We were getting to our desserts when McGrath stood to leave. He ambled to the door, hummed as he circled behind me. I figured I was in the clear, but then he turned 180, pulled a spazzy double-take. “Hey, I know you.”

I bowed my head, excavated the Suez through the meringue of my lemon pie. But good ol’ Mom, she would not stand for it: “Don’t be rude, Leo. Mr. McGrath is speaking to you. He writes for the newspaper, you know?”

My head weighed a ton, the neck hydraulics seized up.

“I do indeed, ma’am. But your son . . . Am I right? Aren’t you the boy who’s friends with that nice little girl—what’s her name?—Annie, is it? Annie Barker?”

“He is,” Mom said. “Tell him you are.”

“I know her family well,” McGrath continued. “Dad owns the lumber yard out on Wooler Road.

Gone hunting with him once or twice. Fine people. Sweet girl. You be sure to say hello for me next time you see her, will ya, Leo?”

I sent my fork to the bottom of my pie and shovelled half into my mouth. I did not chew or swallow, held the pie in the recesses of my cheeks, vacuumed up the remainder from my plate and packed it in, as well.

“What are you doing? Slow down.” My mother shook her head, amused and confused. “And since when are you so shy?”

“Boys will be boys, eh?” McGrath said.

I breathed through my nose, my cheeks expanding, saliva infusing the lemon filling.

“Won’t you join us?” my mother said. “I’ve enjoyed your writing for years.”

“I’d be delighted to,” the psycho said, and signalled for Jack to bring him another coffee. “And one for the lady.”

“So nice of you,” my mother said.

The lemon pie liquefied, trickled into my gullet, the flow intensifying as my mother emptied the vault. Who we were and where we lived. Where I went to school. Where she had worked and what had befallen her best friend, Dottie Lange—or Swartz—and what she was up to now.

“‘Avon calling!’” McGrath said, a playful wink for her, nicotine smarm for me.

“I never would’ve believed I’d enjoy it so much,” she said. “Had I known, I would have started with Avon when I was younger.”

“How’s that possible, Emily? No way you’re a day over twenty-one.”

“Oh, you are a charmer, Mr. McGrath.” Charmer, my ass. Hadn’t Malbasic taught her anything? Letting her guard down with an old fart came to no good. Yet, here she was, flirting to beat the band. You would have thought Cary Grant himself had picked up the tab for her coffee.

“Leo isn’t your brother, then?”

Mom was not naïve. She knew when a guy was on the up-and-up. So I can only conclude she was starved for something beyond the scope of what twelve-year-old me could offer. Bryan McGrath’s corn, I guessed.

He turned thoughtful. “A career change motivated by tragedy. There’s a story there, Emily, if you’d care to have it told. I’m just saying, of course, professionally speaking. No obligation.”

“You must be joking.” Mom was as coy as I’d ever heard her, and hoped to never hear again.

I gagged. Fought the reflex. Popped out of my chair. Charged to the door. “What’s got into you?” Mom cried after me.

“Math homework,” I lied, and the last of the lemon pie hit my gut.

I pushed through the door, the kindly voice of Mr. McGrath on my tail: “Don’t forget, son, you be sure to say hello to Annie for me.”

Ten

From Kingdom Come to Brigadoon

I raged into my bedroom, grabbed the first thing that meant anything to me. The Aurora Wolf Man I’d assembled with glue and care and painted by hand. Busted off his head. Stomped him to Kingdom Come, Plastics Division.

McGrath walked Mom home. I could hear them jabbering outside, caterpillars cocooning in my ears. What was wrong with this picture? I dove onto my bed, face in pillow, pillow baled about my head. He was old enough to be her grandfather. My great-grandfather. What the hell was wrong with my mother? Only then did the pattern occur. Her penchant, Jesus. Bride of Dracula. Bride of Frankenstein. My dad had been an old guy, too. Born in ’05. Dead by ’54. More than a quarter century older than Mom. Those fragments of muffled conversations made sense to me now, Dottie consoling Mom, Mom bemoaning fate and family.

“They couldn’t accept him, Dottie. . . .”

“. . . Alex’s age was just the tip of it.”

“. . . the biggest mistake of my life, they kept saying.”

“. . . him or us, Emily.”

Alexander Berry. Harvey Fucking Malbasic. Bryan Fucking McGrath. What was the point of trying? I could not protect my mother from anything or anyone, least of all herself. She might not have slugged Malbasic with the bronze owl, but I wouldn’t have put it past her if she had. Who next, Old Man Blackhurst?

Mom poked her head into my bedroom. “Did you get your homework done?”

“Yeah,” I muttered sullenly. “I did the math, all right.”

“You want to talk about it?” she said.

“It all adds up.”

“Seems a little early for you to be in bed.”

“He’s a great guy, Mom. Great guy. Best ever.”

She did not take the bait. She never did, bless her heart, which I knew to be a good heart. Her brain was the problem. She began to shut the door and stopped. “What’s that on the floor?” She knelt by my bureau. “Oh, Leo, you didn’t? Why?” she said, as she picked up the pieces of my Wolf Man.

“Even a man who is pure in heart

And says his prayers by night . . .”

McGrath broke into Jack’s garage the same night. He didn’t bother to cover up. He left the two Kit Kat cartons on Jack’s work table, ashes spilled and scattered.

“He wanted us to know he was here,” Jack said.

“Do you think he fell for it?” I said.

“We’ll know soon enough.”

Jack and I backed off on the cards after this. Openly, anyhow. McGrath was a hovering constant in our lives. Perhaps he’d always been and we’d never noticed. We hadn’t given up on the mystery; we revised our strategy, maintaining a low profile until we had a better grasp of the situation or McGrath dropped dead, whichever came first.

If we didn’t have to bother with our parents’ dry cleaning, we would have avoided Mr. Blackhurst, too. Still, we kept it businesslike and when the old guy would show up at the Marquee, Jack made himself busy. Not that Blackhurst appeared to notice. Regulars talked among themselves as much as they foisted themselves upon Jack. Somebody, anybody, to talk to. As though the Marquee was the one place in town they were free to be their old selves. It was harder on Jack, by far. Hollywood North percolated in our imagination, our speculation, relentlessly stalking our conversation. Hollywood North was our Brigadoon, without the sappy singing, the heather on the hill.

Jack gave his time to the house painters and truck drivers, the A&P cashiers and railroad men, the fishermen and office workers, with their facts and stats and trivia, their regrets and anecdotes of minor interest.

Bet you didn’t know the main ingredient in ketchup was originally mushrooms.

Bet you didn’t know hitchhikers in Europe walk with their backs to the oncoming traffic.

Bet you didn’t know locomotives have ice breakers up top to clear icicles from tunnels.

It was the old-timers, though, who came through as always, spurred Jack and me upwards and onwards with their inexhaustible reminiscences, the fun-times they had and the horrors they had lived. They kept The Unknown on the table, our disaster file alive.

We weeded out the ho-hum fires and drownings. By the end of May, any doubts we were onto something were erased for good.

1918 – Ammo plant blows up

1919 – Barn fire and pitchfork murders, 4 dead

1923 – Circus tent burns

1926 – Two sisters murdered on Pelion

1927 – Shoe factory caves in

1930 – Family of three murdered in Hanna Park

1933 – Two girls stabbed to death on Pelion

1937 – Planes crash (Simon Lebel falls to Earth in pieces)

1944 – 51 poisoned, 22 dead at RCAF Day picnic, no cause found, no blame placed

1950 – Boy and girl leap from Pelion water tower

1951 – School bus crash

1962 – Speedboat crash, 6 dead (incl. Dr. Cornish)

While Hollywood North remained out of bounds, at least openly, we continued to pursue our other mystery—the disaster and the amnesia. Why didn’t anyone remember? Asking anyone outright prompted condescending chuckles, amusement at the musings of youth. Worse, when Jack approached those who had related the stories to him in the first place, most denied both the incident and the telling. Jack tried the hypothetical route. “Say there was this town and something really bad happene

d, like an earthquake or an explosion, and a bunch of people got killed. But then, a few weeks or months later, when you ask around, hardly anybody knows what you’re talking about. Like the thing never happened. How’s that possible?”

Only Mrs. Gibbons, the lone survivor of the school bus accident, provided anything resembling coherence. “Because what happened today crowds out yesterday. And personal memories crowd out the impersonal. Look at yourself, Jack, what would you say occupies your thoughts—what you did this morning or what you did in first grade? What-is triumphs over what-was.”

“I see,” he said. “So, then, things like the school bus crash, they’re what-was?”

“What school bus crash?” she said.

Behind closed doors, we also puzzled over the intertitles. McGrath had cowed us, not paralyzed us. We were stubborn little pricks. We’d periodically pull a card or two from the shelves, hoping the answer might leap out, enabling us to expose the threats and lies and diabolical doings McGrath and the town had been up to.

I transcribed the intertitles onto foolscap, a carbon copy for Jack, so it’d be easier to review the cards on our own. I daydreamed the heck out of them, too, imagined myself in the rapture of Eureka!, rushing down Henry Street to bring Jack the thrilling news. Only to have McGrath hunt me down, bleed me, dress me, strap my carcass to the hood of his truck. Then Jack’s carcass. Then Annie’s. Then Blackhurst’s. Then my mother’s.

You fixate on anything as long as we did, expect your unconscious to twist the knife. Weird dreams got weirder. Personalized intertitles flashed with unwelcome regularity through the minefields of our REM. We pledged to report as much as we remembered to one another (taboos and shame permitting) and never speak of same again. We were kids. Subtle we were not. No dream dictionary needed.

The dynamics of our walk-and-talks changed, too. For starters, we invited Annie to come along. Or, as she saw it, we inflicted ourselves upon her.

Outside of the privileges accorded Dufferin’s goody-goodies, Annie and Jack operated in separate spheres and I’d been happy to keep it so: Annie, my school friend; Jack, my after-school. But with McGrath’s threat to do Annie harm looming large, Jack and I felt obligated to protect her. “Not on our watch,” we pledged. Her dad drove her to school most mornings, so that was covered. (Unless McGrath was into car bombs.) So the walk home fell to us. It was the least we could do. Our duty. My duty.

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels