- Home

- Michael Libling

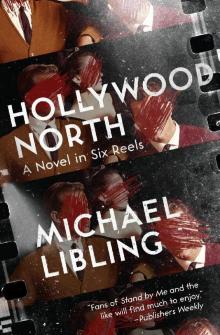

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels Page 16

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels Read online

Page 16

“But do you think he could have?”

She wiped a tear from her cheek. “You remember how flighty Dottie could be.” She dolloped potatoes onto her own plate and sat, elbows propped, utensils in hand. “She tripped. She fell. She drowned. It’s what I was told. It’s what I prefer to believe.”

“Mr. Swartz looks different now.”

“You think so? How?”

“Like he could have done it.”

The light in Mom’s eyes flickered. “You’re saying he looked guilty?”

“Tired. Nervous, maybe.”

“My God, who wouldn’t be, Leo? That makes him human, not guilty.”

“I’m just saying, you know, because people are saying.”

“Well, don’t. Don’t ever. People say many things. They’ve said things about me. About you. Doesn’t make them true.”

“You don’t think he pushed her, then?”

“It is what it is. Nothing can bring Dottie back. She loved Helmut and that was good enough for me. Perhaps she rushed into it. It was quite the whirlwind. If I’ve said two words to the man . . . But I will tell you this, the more you get to know a person, the more you will find to dislike. It’s why I hope, now—especially now—I never do get to know Mr. Helmut Swartz.”

Later, I’d come to see Mom’s theory worked in other ways, too.

The more people got to know me.

The more I got to know myself.

Helmut was too distraught to speak at Dottie’s funeral. Mom was going to tell a funny story about Dottie, but the minister didn’t feel it was appropriate, so Mom just spoke about their friendship and Dottie’s kind heart. As we walked home, I asked Mom if she missed Dottie more than she missed Dad.

“It’s different.”

Mom did not specify how it was different and I didn’t follow up. I missed Dottie more than I’d ever missed my dad. I was afraid Mom felt the same. I wanted Dad to be at the top of her missing list. Because who else was there to miss him, if not her? And if Dad wasn’t missed, he’d be forgotten. And to be forgotten meant you never were.

I do not know if Mom missed my father till the day she died. She did miss Dottie, though. No other friend fully filled the void. Or, more accurately, was permitted to. Not even in Mom’s post-Dottie world where her career path would see her corner the market on friends.

It’s good to lose a parent when you’re young, I think. Maybe not both. But one, for sure. Age five is the cutoff. Three-and-a-half worked for me. The fewer your memories, the less significant your loss. Don’t get me wrong. I felt bad for my dad, but I didn’t know him long enough to miss him badly enough. I missed him for what he missed out on by dying, not for any bond I could recall between us. Memories of my father were spare and suspect, manufactured from photos and fables and counterfeit sit-downs, Dad as Ward and me the Beav.

“Every kid needs a dad” is a myth. You’ve got to have a dad before you can need one and the degree of need depends on the dad you had.

But losing friends. Your peers. I could see why Mom took Dottie’s death so hard. A dead friend could just as soon be you.

Five

Novices on the front lines of puberty

The Sewing Machine Witch was coming down the block as we were scurrying up, and somehow transformed to Iris before our paths crossed.

“Hey, hi,” Jack said. He hoped she’d yet thank us for the bracelet.

“Stay dry,” she said, gathered her cardigan and sprinted past.

“Huh?” I said.

“‘Stay dry,’” Jack repeated.

“What’s that mean?”

“Rain is coming?”

The sky was clear, clouds token.

We’d cut it close. Mr. Blackhurst was twisting the OPEN sign to CLOSED. Jack rapped on the window. The old man pointed to the sign. Jack pulled a long face, laid it on thick. “Please, sir. Just this once.”

I hung back as Blackhurst let Jack in.

“Gus!” Jack snapped, and I followed him inside, watchful, guarded.

“I told your mothers I shut the door at five. No exceptions.”

Jack wasted no time. “You told me they used to make movies here. Were you pulling my leg?”

Blackhurst hitched up his pants. “What’s this about?”

“Show him, Gus.”

I tapped the cards from the envelope. The look on Blackhurst’s face, well, you would have thought a cherished old friend had dropped in to chew the fat. His caterpillar eyebrows arched with devious glee. Slowly, reverently, he reached out. “May I?” he said, and lifted the cards from my hands.

“Sir?” Jack said. “You know what these are?”

“Intertitles,” Mr. Blackhurst said, more to himself than to us. “Never in all my days did I presume to touch the likes of these again.” His accent was hoity-toity gravy, and thicker by the word. Wherever the cards were taking him, he was game for the ride. Blackhurst down the rabbit hole and through the looking glass.

“My friend found them.” Jack urged me forward, his hand at my back, and I shot him a dirty look. I was disinclined to repeat the lie without a sense of how it might go. McGrath had plowed me into a wall. Blackhurst could steam-press me to death.

“Ah, this one,” Blackhurst sighed. “I so fondly remember this one.”

“I wrote it myself for The Black Ace. Nary an iota of lurid violence, yet you should have heard the audiences scream.” He shut his eyes, basked in the memory. “Wholly terrorized, chilled to the marrow, they were. It was marvellous. My magnum opus. Yet it was the infinitely inferior The Lodger that won the accolades. How unjust is that! And only recently, Hitchcock, you know, the man is shameless—the shower sequence in Psycho, stolen frame for frame from Black Ace. The scoundrel thought no one would know, thought sufficient time had elapsed. But I know. We know.”

“And this down here?” Jack said, indicating the logo.

“Blackhurst Pictures International, of course. My production company. Alas, as ill-fated and lamented as the others—Canadian National Features, Adanac, Pan American Films . . .”

“So it’s true, then—they did make movies in Trenton,” Jack said, and my excitement was every bit as palpable as his.

“Hollywood North, right, Mr. Blackhurst?” I said, eager now to be a featured player. “I found them. It was me who found the intertitles. I’ve got a bunch of them, you won’t believe.”

“Thing is,” Jack said, “Mr. McGrath, over at the Record, he told us we needed to burn them. Why would he—”

“I beg your pardon? McGrath? Bryan McGrath?”

“Yeah. Like he was scared of them.”

“It was really, really weird,” I said, thriving on the upswing.

“McGrath, the great saviour. Why in Heaven’s almighty name would you share a discovery of this magnitude with a knave? A more egregious overreactor I have never known. Burn them? Quintessential McGrath. A nervous Nellie of the first order. A mediocre and malodorous screen scribe transmogrified to mephitic muckraker. My dear lads, your intertitles are but memories of a bygone era. The man’s worries are woefully misplaced.”

“So there is something to fear, then, sir?” Jack said.

“Isn’t there always, my boy?”

“You’re telling me,” I said with a laugh. By now, I was fully on board with the new, enthusiastic version of me.

“Can we see the movies?” Jack asked. “Do you have them?”

“Norman.” We turned to the rear of the shop and the voice of a woman.

Mr. Blackhurst hastily drew us back. “She will tell me I have said too much. Alas, to you, I will have said too little. No matter what you may hear, it was not the talkies that killed Hollywood North, it was indeed, as you have surmised, the fear.”

“That’s enough, Norman. Enough.”

“Perhaps a close-up now, gentlemen, a wistful glance to the right, focus soft, and cut to the intertitle. ‘He had dreams, you know. Hail the Revered Masters! F.W. Murnau. D.W. Griffith. C.B. DeMille. And if not for i

gnorance, delusion, and myth, the redoubtable N.K. Blackhurst.’” He winked at me. At Jack. And aged ten years in ten seconds. The cards sailed to the floor and some of his brain, too. His expression went from blank to black, Dr. Jekyll awakening to find Mr. Hyde’s bloody cane in his hands.

“Sir?” Jack said, but the man had hopped the fast freight to Voodoo Island. In dull retreat he dragged his feet and exited behind a curtain of cleaning.

I dropped to my knees to gather up the cards. Jack skirted the counter in pursuit.

“Let him be,” the woman said, gentle, then assertive: “Let him be.”

I rose gingerly to my feet. Holy cow. And wow! It was the woman. It was her. Minus the fur.

She stood square with Jack, ravishing and resolute, a vision to behold in black silk and pearls, with raven curls falling softly to slight shoulders. She was Helen of Troy relocated to a dry-cleaning shop in Trenton, Ontario, Canada. A cruel twist of Fate, for sure, even discounting the lousy winter weather.

Jack edged away. I’d never before seen him anywhere near flustered. His footsteps were jittery in keeping with his stammer. “You must be Mr. Blackhurst’s daughter . . . uh . . . um . . . wife . . . uh . . . daughter . . . uh . . . Jesus help me, I’m so sorry, so sorry, Miss, Missus, Ma’am, Missus, Ma’am, Miss . . .”

The lady was either the youngest old person I had ever seen or the oldest young person. Whatever, she was way too pretty for this town. Hell, a dream come true, she put my mom to shame; next to her, Mom was a beard shy of sideshow. This woman was nobody’s mother, nobody’s sister. And it was her, all right. The woman I remembered. It was her.

“Excuse me.” I raised a hand, thinking this an opportune moment to impress. “Did Mr. Blackhurst tell you? It was me. I’m the one who found them, aren’t I, Jack?”

She folded her arms, slender fingers and scarlet nails extended to opposing shoulders, and raised her chin in expectation. The expectation we would leave.

“Do you remember me?” I said. “I saw you one—” And those blue eyes of hers, goddamn, way bluer than any blue was meant to be. I swallowed. Could not stop swallowing.

We did not want to leave. We wanted to stare.

She observed us with contained impatience, bending us to her unspoken will. And those heels of hers, goddamn, they must have run halfway to Heaven.

Poor Jack and me, drawn and quartered, mere novices on the front lines of puberty. And those red lips of hers, goddamn, way redder than any red was meant to be. We could not breathe.

The door jangled shut behind us. The shop went dark.

We lingered outside the cleaners, in no rush to shake her spell. Whatever it was she’d stirred in me was nothing I wanted to end. When our legs got around to moving, it was more a result of the Earth’s rotation than a desire to move on.

“That was her,” I said, stating the obvious. “The lady I told you about. In the fur coat. The woman who acted like she knew me. I told you she was real.”

“She sure didn’t act like she knew you now, did she?”

“Do you think she’s his wife? She could be his wife.”

“And Mr. Blackhurst, what he said, the movies, Hollywood North . . . He was telling the truth, you could see.”

“He loved the cards.”

“But McGrath, and now her, getting all worked up over . . . Over what, man?”

“History isn’t supposed to be a secret.”

“And it isn’t supposed to be forgotten. At least not by the people who only just lived it. Not this quickly.”

“Your mass amnesia theory makes more sense by the second.”

“Nah. Nothing makes sense, man. Not without the why. We know about Champlain and the Indians climbing Mount Pelion. They taught us that much, right? That sort of history. So it’s not everything. It’s the more recent stuff.”

“The bad stuff.”

“The accidents, sure, but why the movie cards? A movie studio? Where’s the bad in that?”

“Makes you wonder how much more they’re hiding from us.”

“Hiding? Or forgetting?”

“Could be both. Like dogs who bury their bones and next day can’t remember where.”

“We need to keep our eyes open. And we need to be careful. I mean, what if you and me—what if we start forgetting, too?”

“I won’t forget her, that’s for sure.”

“She was something, all right.”

“I told you, man. I told you.”

Six

Mom on the move

“Movies?” Mom stifled a giggle. In the wake of Dottie, anything resembling happiness was cause for optimism. “A studio? Here?”

“A long time ago. Mr. Blackhurst was telling us. . . . His wife, she was there, too.”

“Don’t tell me the sewing machine lady has finally spoken?”

“Not her. Another lady.”

“What other lady?”

“And Alfred Hitchcock—”

“He was there, too?” Her giggles ran fast and loose, now.

“No. No. But Mr. Blackhurst knows him. He’s friends with him. Okay, not friends, because Alfred Hitchcock stole from—”

“My goodness, sweetheart, what are you going on about?”

I caught myself, realized how I must have sounded. I replied softly, “Nothing. I guess.”

“Are you feeling all right? It hasn’t been easy lately, I know. For either of us.” She patted the top of my head, squeezed me tight, as if the nonsense inside of me was ketchup. “Mr. Blackhurst is a very nice man. But he can also be rather odd. I would not put it past him to make up the occasional tall tale. He was only teasing you.”

I laughed convincingly. “I know. You’re right.”

“The whole idea is so farfetched. If it were anything more, we would have heard, don’t you think?”

“Like there’d be historical markers or something.”

“Exactly.” Her grin remained on standby. Again, I was glad to see it, yet also hated when she humoured me; to her I’d be three years old forever. “It’s important to respect seniors, Leo, but to believe everything . . .”

“I know he was being silly. I just thought—”

She perked up, bustled me to arm’s length. “Hey! I’ve got news, too.” More and more, she was returning to her old self, moving beyond Malbasic and Dottie. “I quit my job. I’m going to be an Avon Lady. What do you think of that?”

The office was cluttered with too many memories, work no longer fun without Dottie, though I never saw how work at the Unemployment Insurance Office could have ever been fun.

“You’ll be ringing doorbells?” I said.

“‘Avon calling!’” she chirped.

“You sound like the TV commercial.”

“You think so?”

“I swear, Mom. You’re going to be good at this. Bet you anything.”

Seven

Another unexplained mystery to call our own

Frank and Joe Hardy. Damn right we were.

All week long we collected cardboard, whatever we could find—from shirts and whatnot. When the stack equalled the height and volume of the forty-seven movie cards, we burned the cardboard and divided the ashes between two Kit Kat cartons. Jack labelled them same as he had the other finds on his shelves, by content, date, and rating. He gave them an X. And then, to make the lie complete, he added:

MOVIE TITLE CARDS

Found by Gus, Hanna Park, April 1962

“We need to leave them where McGrath can see them. Easy, but not so easy he’ll see we’ve set him up.”

Jack cleared a spot next to the box where the meteor had been stored, before he donated it to Queen’s University. All he’d kept were photos of the meteor. And meteor dust. “Alphabetical order,” he explained.

We waited till Saturday morning when my mom was at the A&P and Jack’s parents were at the restaurant to make our next move. We secured the cards beneath the false bottoms of two board games, Risk and Concentration, and smuggled them from Jack

’s garage to my house. We figured they’d be safer there. McGrath didn’t know me from a hole in the wall, not like he knew Jack. Besides, he rightly suspected it was Jack who’d found them. We saw that.

The worry he’d kill my mother had subsided. Mostly, anyhow. Jack had put me at ease. “Me and my family are way better targets.” McGrath was a Marquee regular. “If he’s going to hurt anyone, he’ll start with us.” The trick was to make him believe he’d scared the crap out of us and we’d destroyed the cards. Jack was certain he’d come snooping, follow up on us.

We pushed back the coffee table, the armchairs, and sofa, and spread all forty-seven across the living-room floor.

We spent a good couple of hours, struggling to make sense of the words, come up with a coherent sequence.

We reordered the cards every which way. Read them aloud two, three, four times, listening to each other for clues, searching for a breakthrough.

Some went together more than others, raising our hopes.

But try as we might, we could find no red flags to justify why McGrath went psycho or why the Blackhursts had circled the wagons. No Rosetta stone to pave our road to fame and fortune.

“The answers are in front of our noses,” Jack said. “It’s going to come, you’ll see, when we least expect it.”

“If we could see the movies . . .” I said.

“Till then, another unexplained mystery to call our own.”

We buried the forty-seven among the books of my father’s library. I slipped the last between the slippery pages of Lithuania and Luxembourg in a Hammond World Atlas.

“You sure your mom won’t find them?” Jack said.

“My dad was the reader.”

“A big one, too, from the looks of it.”

“He died in the War. On Juno Beach.”

“Wow. Like Mrs. Bruce’s son. You know, the old lady whose wedding ring I found.”

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels