- Home

- Michael Libling

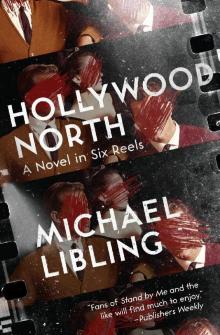

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels Page 9

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels Read online

Page 9

“You will.”

“I won’t.”

“You remember Mrs. Gibbons, used to teach third grade?”

“Crabby Gibbons. Yeah. I was lucky. The fatty quit before I got to third.”

“When she was a kid, she built her own soapbox, except they wouldn’t let girls enter the derby back then. So she dressed up as a boy, pretended to be her own brother, and won the whole caboodle.”

“What’d she use, a refrigerator crate?”

“Look, I’m telling you what people tell me. But if you’d rather joke around—”

“You’re not telling me anything, man. You don’t want to? Fine. Don’t. Keep your stupid secrets.”

“Jesus, what’s got into you?”

I had Mrs. Dahl-Packer gunning for me at one end and Jack giving me the runaround at the other. Like they were better than me. Like I wasn’t good enough to be a finder, a finder-outer, a human being. What had Mrs. Peckerface called me? A troglodyte. She had me pegged. It’s all I’d ever be. Jack was treating me the same.

I swerved into the street and hit the brakes. Double Al, Dandruff Wayne, and a toothy trainee awaited me with open arms on the other side.

“Come. Come. Come and get it,” Double Al taunted, as Dandruff Wayne performed his caged-gorilla bit and the trainee mimed my fate should I comply. But then Double Al tripped into the trainee and the trainee fell off the curb, and I broke the cardinal rule, laughed out loud.

Double Al had taken to wearing his boots untied, bows too sissy, and woe to anyone entertained by his frequent stumbles.

I split my sides, strived for the hilarity level of a live studio audience and me the dick they cut to for the rollicking close-up.

I’d had it up to here with the suspense of when and where the bastards would move on me. They wouldn’t kill me. Bullies maimed. I had Jack’s assurance. My suicide would be a partial. Best of all, my blood would be on Jack’s hands. By holding out on me he’d forced my hand, led me straight to Double Al.

I hunkered down, faked them out, exploded from my squat, swift, slick, and lethal, haymakers and windmills. Al, the sap, he never saw me coming. I propelled him into a maple and kindly rearranged his face. Oh, man, you should have seen his buddies run. Gratitude poured in from every corner. By day’s end, I’d been hoisted onto shoulders, paraded up and down Dundas, and handed the keys to the city, a statue to be erected in my honour.

How I wish.

I hunkered down, readied for the blows to hail. Jack reeled me back onto the sidewalk. And before I could protest, he did the nuttiest thing I’d seen outside a Jerry Lewis picture. He raised a fist, and with his right arm bent to ninety, he gave his bicep two quick chops, and hollered a guttural and fearless, “Vaffanculo! Vaffanculo!”

Hey, think I was confused? Double Al and his bozos were fit to be tied. They were coming for us and they weren’t, steps forward, steps back, scuffling on and into each other, arguing, swearing, shoving, and Jack and me shunted to second feature. By block’s end, Double Al had socked both Dandruff Wayne and the trainee, and the three had gone their separate ways.

“Holy cow! What was that?” I said.

“Don’t you know that about Double Al? He needs to outnumber you by at least two to one.”

“No. What you said?”

“Oh, that. Yeah. It’s Italian. A curse or something. There’s this truck driver, Mr. Canova from Toronto, comes into the Marquee whenever he passes through. He said if I ever needed to put some asshole in his place, see how bullshit baffles brains—”

“It’s magic then? Like a spell?”

“I guess. But it only works if you do the arm thing, too.”

“Vaffran-what?”

“Culo. Vaf-fan-cu-lo.”

“Vaffanculo.”

“It’s not the word so much, Gus. It could be anything. I told you, it’s about keeping them off balance. The less predictable we are to them, the more predictable they are to us. Like when you were laughing, stuff like that, it throws them off somehow.”

“That your plan for me, too? Throw me off, keep everything to yourself.”

“You don’t give an inch, do you? Cool down. Have a little patience. I was getting there, I swear. There’s a lot to get your head around. I wanted to ease you in.”

“I’m as eased in as I’ll ever be.”

“Yeah, we’ll see.”

“Yeah, we will.”

“You asked for it.”

“Hurry it up.

“Thanksgiving Day, 1918. There used to be this big plant down by the river. It made bombs and bullets and whatever for the war. That’s the day it blew up. Thanksgiving, 1918. Took out half the town.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Right here. Trenton.”

“Bullshit. I never heard about anything like that.”

“It’s only the tip of it.”

“Tip of what?”

“The bad stuff, man. People love telling me the bad stuff most of all.” He sped ahead with a tour guide gait and I followed, searching streets and backyards for ruins or whatnot.

“Winter, 1927. Walker Shoe Factory. The roof collapses under heavy snow. Almost thirty dead. . . .” He rattled off the facts and fatalities, revealing the workings of his brain. Jack was a categorizer. He cut through the clutter, broke stories down to relevant components.

I could have been watching You Are There, with Jack instead of Walter Cronkite. “October, 1937. Two planes crash into each other over town. Bodies drop out of the sky. Body parts . . . Summer, 1923—”

“Wait. Wait.”

“Wait what?”

“Body parts?”

“All over the place. The guy who tells me, he says his son was one of them—a co-pilot. His head turned up in one place, and his middle in another, and his legs someplace else. And then the old man started bawling, because some of his son was never found.”

“He cried?”

“Old men cry easy. You should see.”

“Jeez.”

“Summer, 1923. The circus comes to town. The big top catches fire—”

“And what? Lions and tigers got loose and ate people? Elephants stampeded? I saw that movie. C’mon, eh?”

“Hey, I don’t care if you believe me. You wanted to know and I’m telling you. You don’t want to listen, makes no difference to me. Look, I know where you’re coming from. Some of the people, some of their stories . . . There’s this Mrs. Wimmer from Austria. When she was a kid, Adolf Hitler was her babysitter. She says he did things to her.”

“What things?”

“When her father found out, he beat him to a pulp—came this close to killing teenage Adolf.” Jack put on this old-lady voice. “‘Mein fotter vood huf saved da vorld!’”

“I’ve seen her in the restaurant. My mom talks to her.”

“My dad says she’s a liar, and she’s only trying to cover up her own guilt for whatever it was she must have done in the war.”

“But what if her father really had killed Hitler?”

“You’re a what-if guy, eh?”

“Aren’t you?”

“I’m more what-was. You want more?”

“How much you got?”

“Yesterday afternoon, Mrs. Gibbons is having her tea and calls me over. I figure it’ll be the soapbox saga again. But no. ‘A story I’ve never told anyone,’ she says. And this one, Gus, I’m warning you, once it’s in your head, there’s no going back.”

“C’mon . . .”

“You were born what—’51?”

“In May.”

“Same year. June. Last week of school. A school bus comes down King. Kids packed in like sardines. They’re going on a picnic. Except the bus loses its brakes same time a train is going through the crossing at Division. . . .”

“Jesus.”

“Mrs. Gibbons is sitting on the bench at the rear of the bus with another teacher. And she thinks the world has come to an end. Crashing. Smashing. Screaming. Glass breaking, flying. So much noise she

can’t hear the noise. She blacks out. And when she comes to, she’s still on the bench. But it’s all blurry and smoky and dusty and bloody around her. And the teacher who was sitting with her, she’s gone. The whole bus is gone. Nobody and nothing left. Only Mrs. Gibbons on the bench. And there’s a foot in her lap. A small foot and it’s wearing its shoe. A red shoe. A girl’s shoe. Mrs. Gibbons cannot move. The Russians went and dropped the bomb, she’s sure of it.”

This was better and worse than anything I’d expected. We’d arrived at my house, but I wasn’t going anywhere.

“They had to go by the dental records to identify the bodies. . . .”

“Like on TV.”

“Except some of the kids had never seen a dentist. There was no telling who was who. And, get this, some were buried with pieces of glass and metal still in them. And they had to have funerals for parts of the bus, because they couldn’t get all the flesh and guts out of the twisted and melted parts.”

We moved to my stoop. Sat.

“Mrs. Gibbons didn’t have a scratch on her. Nothing. Except she shows me this little bump on her arm. I’m the only person she’s ever shown it to. It’s right here. See. Below her shoulder. A yellowy purple bump. The size of a quarter. She swears there’s bits of bus and dead kid in there, because at night, the dead kid, she calls out to her.”

“Holy shit.”

“I warned you.”

“Calling out what? ‘Help! Get me out of here.’”

“More like a question. Different words, but always the same. The kid—Mrs. Gibbons thinks it’s the girl who lost the red shoe—she wants to know, ‘How come a nasty old teacher like you got to live and me and my friends are dead before we started?’”

“No way.”

“Swear to God.”

“And the girl, it’s talking from inside of her? Her arm?”

“Since the bus crashed.”

“Like she’s haunting herself, almost.”

“Mrs. Gibbons wants to kill herself.”

“Wow.”

“She’s wanted to for years. But she worries it’ll be unfair to the dead girl inside her arm. She’d be killing the kid a second time.”

“She could cut the bump out of her arm, keep the girl in a jar or something, couldn’t she?”

“Like in Donovan’s Brain.”

“That’d be so neat.”

“I’m not so sure.”

“What’d your mom say? Your dad?”

“I asked if they’d heard about the school bus. I didn’t go into details. Nothing about Mrs. Gibbons or her arm. My parents have enough problems without thinking their son needs a straitjacket. Truth is, I probably do. I tell you, Gus, some of the stories . . . The old people, it’s like they’re desperate for me to know. Like they’re afraid to go to their graves without sharing the secret. Since the newspaper started writing me up, you’d think I was their best friend. Nuts, eh?”

“Yeah.” I saw Jack as my best friend, too, right then. “Nuts.”

“Mom said she remembered something about a school bus, but I could see she really didn’t. She does that a lot. And then her usual: ‘Why can’t you think nice thoughts?’ I didn’t bother with my dad. He’d only tell me I was watching too much TV.”

“I get that from my Mom, too.”

“So many accidents, eh? Weird stuff. And nobody seems to remember any of it.”

“Except the people who tell you.”

“And we’re just one small town here. I thought maybe it was a Candid Camera thing, like they were seeing whose baloney could spook me out the most. So then I asked Bryan McGrath—the reporter at the Record, the guy who writes about me finding things. If anybody would know, it’d be him.”

“And did he?”

“He laughed, said he wouldn’t have a job if bad stuff didn’t happen. ‘More the better.’ I asked if I could go through the old papers. They’ve got these microfilm readers. He got all serious. Told me if I liked horror stories so much, I should buy Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. Besides, according to him, the Record archives only go back to 1955, because of Hurricane Hazel, the big flood and fire.”

I knew about Hazel. A branch broke off a tree and shattered my bedroom window. It was the Halloween before my dad got killed.

“And then he warned me, said I’d be wise to take whatever the old coots say with a big grain of salt or I’d end up as empty-headed as them.”

“But he didn’t say if any of it was true or not.”

“That’s the thing.”

“They gotta be, right? People don’t make stuff like that up. Not about dead kids. Nobody likes talking about dead kids. Except kids.”

“I’m with you, Gus. Maybe not every story I hear, but most. . . . The way they tell them to me. The look on McGrath’s face when I brought up the ammo plant, the planes colliding—like he’d been caught in a lie, like there was stuff he didn’t want me knowing.”

“Jack, if I tell you something, you promise not to laugh?”

“Not unless it’s a joke.”

“Since I was little, I’ve had this bad feeling—”

“As bad as having a dead girl living in your arm?”

“It’s hard to describe. It’s like something’s going to get me and—”

“. . . And there’s nothing you can do to stop it.”

“Jeez, yeah. Like what’s going to happen is going to happen.”

“Me, too, Gus.”

“You swear?”

“On a stack of Bibles. You know The Twilight Zone is about Trenton, don’t you?”

“Huh?”

“Trenton is The Twilight Zone.”

“Now you’re really kidding. . . .” A whole new bad feeling rose up inside—that everything he’d told me had been a lie, that I’d be the laughingstock of school by morning.

“Rod Serling. He’s from Syracuse or Rochester or somewhere.” Jack nodded in the direction of Lake Ontario. “He’s been here a bunch of times, comes across on his cabin cruiser. I’ve met him.”

“Liar.”

“Honest to God, Gus. At the town dock. My parents, they’ve got these old friends from Erie. He’s a doctor and she plays the harp or whatever. Two summers ago, they show up on their yacht. We’re over there visiting, and the boat is neat and all, but soon I’m bored out of my mind from hearing about the good old days, so I go out and snoop around the dock. And there he is.”

“Rod Serling? Twilight Zone Rod Serling?”

“Bending down, checking the lines.”

“Bullshit. Bullshit. Bullshit. Up yours, man.”

“I’m telling you . . .”

“And you talked to him?”

“First time I only stared.”

“First time?”

“Next morning, I went back. He was sitting on his deck.”

“Aw, c’mon . . .”

“I said, ‘Are you Rod Serling?’”

“And him? What’d he say?”

“‘Last time I looked, son.’”

“That’s it?”

“That’s it. Swear to God. Swear on my sisters’ lives.”

“Did he know who you were? Did you tell him you were Jack the Finder? Wow! What if he does a Twilight Zone about you, Jack? Or Mrs. Gibbons and the girl in her arm?”

“I’m just trying to tell you, he knows the town. And I bet you anything he’s gotten a bunch of his ideas right here. Watch the show, you’ll see. Some of the episodes, you’ll swear, they’re documentaries.”

“I hate documentaries. You ever see the one on herring fishing?”

Four

Good Deed Gus

“So, you finally have a best friend,” Annie said.

“No I don’t,” I said.

“You’re always with him.”

“No I’m not.”

“I’m not arguing with you. I’m happy for you.”

“I got best friends. Lots.”

“Has he showed you how he finds what he finds?”

“H

e will.”

“He doesn’t talk much, does he?”

“Yeah, he does.”

“As much as you?”

“I talk.”

“That day, when the park ranger brought the new badgers to school, and a bunch of us got to see them before everybody else, Jack Levin didn’t say a word to me.”

“Yeah? So? Did you say anything to him?”

“He kept to himself.”

“He’s not like that.”

“He sure knows a ton about badgers.”

“I thought you said he didn’t talk.”

“He did, I guess. But it was more like showing off how smart he is to the teachers and ranger.”

“Jack is smart. He knows something about everything.”

In first grade, Annie sits at the desk behind me. She pokes me in the back to borrow my pencil sharpener, my ruler, my opinions. Usually with her finger. If she’s feeling lazy, with her pencil. The eraser end. “Gus, Gus. Psst, Gus . . .” Miss Proctor tells Annie to mind her own business once a day. Miss Proctor never sends anyone to the office. She doesn’t have it in her.

Next year, Annie sits to my right. She bites her lower lip when she draws in art class. She taps the tip of her nose when adding and subtracting. This is all new to me.

Come third and fourth, she takes the desk ahead of me. When she turns to talk, it’s sometimes part way around, more often all the way. Depends on the urgency of her news, jokes, observations, the temper of her counsel, her psychotherapy and editorials. It’s the way she turns I love the most, the movement of her hair, shoulder to shoulder, the shape of her lips the instant before she whispers, and how her eyes conspire with her whispers. I was supposed to hate girls. And all I ever wanted was to hug her.

Our shared sense of doom is where Jack and I truly bonded.

My breakfast with the Trent Record went from daily chore to daily obsession. I combed the pages, scoured the obituaries and in memoriam notices. My aim was to expand Jack’s list or, at least, lend credence to the stories he’d been told. My mother, in her doting oblivion, was thrilled by how I’d bolt for the paper as it smacked the stoop. She was forgiving when I whined for sections or accused her of hogging. The scissors and notepad I kept at hand awed her no end (though clippings and notes of any substance amounted to none). Mom never had to say a word. Her pride was her corsage: Young Churchill’s mom would have begged to have been so blessed.

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels

Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels